“In my first class at MIT, I arrived 10 minutes early to a lecture hall…only to watch wave upon wave of male students walk in behind me. I was confused and curious. Where were the women?” This narrative, found in an article from Times Higher Education, is from Irene C, an electrical engineering and computer science student at MIT. In a report released in 2017 by the Office of the Chief Economist, “Women filled 47 percent of all U.S. jobs in 2015 but held only 24 percent of STEM jobs.” The report also asserts that “women constitute slightly more than half of college-educated workers but makeup only 25 percent of college-educated STEM workers” (1). This situation has occurred because female students in STEM (Science, Engineering, Technology, and Math) face multiple obstacles, such as being discouraged by systematic oppression from their mentors, fellow students, and society itself. One such narrative of oppression from an article found in the Huffington Post puts the situation into perspective: “In high school my guidance counsellors (both male and female) said that I wasn’t smart enough to get into [an] engineering [program] and that even if I did I wouldn’t be able to complete the program and get a good job or one that pays well.”  The narrator then proceeds to talk about how “They encouraged me to go to college for an engineering technician program instead because it was easier and there were more girls there . . . I’d just started my first year of engineering at one of Canada’s best engineering universities, no thanks to any of the guidance counsellors or careers teachers at my high school” (2). Unfortunately, not all stories like these have a happy ending. More often than not, an cycle emerges that facilitates the process of pushing female students away from STEM fields. Girls are told they “aren’t smart enough” and that they should be pursuing a career that is considered more suitable for their intelligence, skill levels, and societal standing. After being exposed to this type of thinking as early as elementary school, a large number of female students begin to believe that this mindset is true, and thus begin to turn away from STEM based careers when deciding what paths of study they want to pursue.

The narrator then proceeds to talk about how “They encouraged me to go to college for an engineering technician program instead because it was easier and there were more girls there . . . I’d just started my first year of engineering at one of Canada’s best engineering universities, no thanks to any of the guidance counsellors or careers teachers at my high school” (2). Unfortunately, not all stories like these have a happy ending. More often than not, an cycle emerges that facilitates the process of pushing female students away from STEM fields. Girls are told they “aren’t smart enough” and that they should be pursuing a career that is considered more suitable for their intelligence, skill levels, and societal standing. After being exposed to this type of thinking as early as elementary school, a large number of female students begin to believe that this mindset is true, and thus begin to turn away from STEM based careers when deciding what paths of study they want to pursue.

However, studies and research projects on the topic of female ability in STEM have proven this way of thinking is actually false. Katherine Weber, a Gender Equity Specialist and Independent Education Consultant, asserts that “It is important to note that there are barriers that discourage female participation, including their own negative perceptions of their abilities in STEM” (1). These barriers and negative perception towards their own abilities contribute to the hesitant attitude that many female students develop towards STEM fields. According to a study conducted by Weber, both male and female students in middle and high schools had equal academic performance in STEM subjects, and used STEM-based resources equally. However, male students perceived that they had higher capabilities in STEM subjects than female students did. The results found in this study give rise to a plethora of questions surrounding this stigmatization of female students in STEM, including why this cycle of objectification towards females in STEM continues in today’s society (23). This is a never-ending narrative of struggle and marginalization for female STEM students that has to be addressed, and soon. But what exactly is keeping female students from entering STEM fields, and what needs to be done to fix this problem? Gender studies specialists, psychologists, and education experts have studied the factors that prevent female students from entering STEM fields, especially in middle and high schools where this phenomenon begins to have a major influence. Some studies that analyze this issue through how it affects females and their performance in the classroom have begun to produce potential solutions to this serious issue.

There are several factors that contribute to the discouragement of the participation of female students in STEM fields. There is even evidence that motivational factors that reflect the personal interests and mindsets of women, along with sociocultural factors like stereotypes and biases, can affect the choices a woman makes regarding career choices. Psychologists Ming-Te Wang and Jessica Degol from the University of Pittsburgh have come to the conclusion that there are six main factors that cause female under-representation in STEM fields. These six factors, as asserted by the authors, are cognitive ability, relative cognitive strengths, career preferences, lifestyle values, field-specific ability beliefs, and gender-related stereotypes and biases (121). During this study, Wang and Degol accumulated sources that focused on the issue of women in STEM, and analyzed them based on the six factors mentioned above. They assert that “sociocultural factors, such as societal beliefs and expectations of male/female differences in ability are far more likely than biology alone to impact career decisions.” The authors assure readers that “While these findings. . . highlight the continued existence of rigid, flawed, and narrow views of what it means to be male or female in our society, as with most research there is a silver lining. The fact that sociocultural factors have such a strong influence over individual career decisions also means that we may intervene to alter these outcomes” (129). This study then proceeds to discuss different solutions for this issue, such as generating earlier interest in STEM in girls and providing them with a mentor that encourages them to pursue a STEM education (130-133). It is easy to see in this report just how these factors leave a deep impact on females, and what they have to consider when making choices about their future. Through their review, Wang and Degol create a cumulative report on the factors that affect female under-representation in STEM, and provide a clear framework for grasping the severity of the situation.

Many of these factors seem like they would affect female students at a later point in life. However, they actually begin to influence girls as early as middle school, causing them to lose interest in STEM early in their academic careers. This factorial influence can have permanent consequences on the choices females make regarding their future fields  of study and possible job choices. A study published by Ryan Brown et al. in Technology and Engineering Teacher supports this claim as “the participation and success of females and males in STEM courses generally begins on equal footing in Grades K-6,” the authors inform readers, “there is a trend that females participate in STEM courses less as they progress through Grades 7-12” (29). To find these results, the authors took data from other studies and compiled it in order to come to the conclusion that female students withdraw from STEM in middle school. This conclusion about the ages at which female students withdraw from STEM gives evidence that this period of middle school into high school has a strong influence on the choices female students may make about the futures they have.

of study and possible job choices. A study published by Ryan Brown et al. in Technology and Engineering Teacher supports this claim as “the participation and success of females and males in STEM courses generally begins on equal footing in Grades K-6,” the authors inform readers, “there is a trend that females participate in STEM courses less as they progress through Grades 7-12” (29). To find these results, the authors took data from other studies and compiled it in order to come to the conclusion that female students withdraw from STEM in middle school. This conclusion about the ages at which female students withdraw from STEM gives evidence that this period of middle school into high school has a strong influence on the choices female students may make about the futures they have.

Along with age, the authors of this report also claim that the surroundings in which a student learns can have a direct impact on how he/she will respond and behave. When considering the environment in which a student is learning, the authors assert that it is important to consider “The decor in a room, language on a test, gender-identifying questions preceding a test, and what students are told the test is measuring.” The authors then provide suggestions on how an instructor can improve the environment of a room so female students feel more welcomed. One of these suggestions includes making “classroom guidelines that foster student interaction, respect for others, and insightful questioning.” The authors also advise that teachers “Keep negative opinions, attitudes, and stereotypes about females in STEM out of the classroom, including your own” (30). If a female student does not feel secure enough in her environment to participate in activities based on STEM, she will not engage as much and could even be deterred from pursuing other STEM related courses or careers in the future. The suggestions provided by Brown et al. can assist in remedying this issue, and make females feel more welcome to participate in their STEM courses.

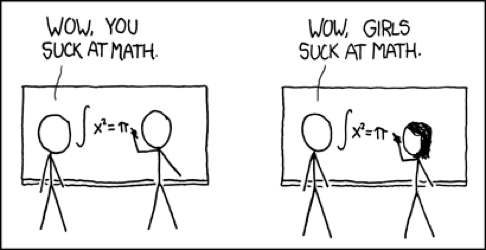

From these studies on the different factors influencing girls’ choices to enter STEM fields, one main variable has shown up in one form or another: stereotype threat. This phenomenon is an issue that has been a constant obstacle for female students in STEM fields, as it can affect their performance on assessments. A more specific definition of stereotype threat, according to psychologists Markus Appel, Nicole Kronberger and Joshua Aronson, is “an  uncomfortable psychological state that has been shown to impair cognitive ability test scores,” and has been shown to have an influence on processes involving learning and knowledge acquisition, mostly in regards to female students and their performance on math and science tests (1). The article outlines studies conducted at four universities across Germany and Austria, which placed female and male students in situations where they gathered data about STEM from different articles, took a test about different STEM fields, took notes about a STEM subject, and evaluated other students’ STEM notes as well. The authors then analyzed the data gathered from these studies and came to the conclusion that “people are aware of a stereotype portraying women as less proficient in STEM-test preparation than men…women’s note-taking activities were impaired under stereotype threat…[and] stereotype threat impaired women’s performance evaluating the notes of others” (905-910). These results led Appel et al. to the conclusion that stereotype threat not only hinders stereotyped individuals’ capacity to demonstrate their abilities but also impairs behaviors that develop them. Stereotype threat is a serious issue that needs to be addressed, both in the classroom and in society itself. However, if the suggestions given in the study published by Brown et al. are applied to the scenarios developed in the studies conducted in this essay, it is possible that the results found by Appel et al. would not have been so divisive between females and males as that stereotype would have been diminished.

uncomfortable psychological state that has been shown to impair cognitive ability test scores,” and has been shown to have an influence on processes involving learning and knowledge acquisition, mostly in regards to female students and their performance on math and science tests (1). The article outlines studies conducted at four universities across Germany and Austria, which placed female and male students in situations where they gathered data about STEM from different articles, took a test about different STEM fields, took notes about a STEM subject, and evaluated other students’ STEM notes as well. The authors then analyzed the data gathered from these studies and came to the conclusion that “people are aware of a stereotype portraying women as less proficient in STEM-test preparation than men…women’s note-taking activities were impaired under stereotype threat…[and] stereotype threat impaired women’s performance evaluating the notes of others” (905-910). These results led Appel et al. to the conclusion that stereotype threat not only hinders stereotyped individuals’ capacity to demonstrate their abilities but also impairs behaviors that develop them. Stereotype threat is a serious issue that needs to be addressed, both in the classroom and in society itself. However, if the suggestions given in the study published by Brown et al. are applied to the scenarios developed in the studies conducted in this essay, it is possible that the results found by Appel et al. would not have been so divisive between females and males as that stereotype would have been diminished.

Changing the environment of a classroom to welcome female students into STEM has already been discussed by Brown et al., but it is important to take into account perceptions of the teachers and male students towards female students as they are interacting in the classroom. While it is one thing to consider the classroom environment itself an influencer, if female students feel they are being viewed in a stereotypical way by teachers and peers, they can be deterred from participating. In their research paper, sociologist of education Catherine Riegle-Crumb and research data analyst Jenny Buontempo, along with psychologist Chelsea Moore, discuss whether interactions with a female teacher and female peers in a high school engineering classroom decrease male students’ gender/science, technology, engineering, and math stereotypical beliefs and whether this varies according to the initial strength of their stereotypical views.  They focused their study on high school engineering classes, which “represent a relatively new advanced course offering available in approximately only 10% of schools nationwide.” The authors chose engineering classes as they offer an ideal location to study the “stereotypical views of young people and how they change” and also represent the typical ratio of female to male students (493). STEM elective courses are typically comprised of students interested in pursuing a STEM major in college, thus high school engineering courses have relatively fewer female students on average. The study gauged the effects of stereotypical perceptions on both male and female students at the beginning and end of an engineering class, and analyzing how much their perceptions of each other had changed or remained the same. The researchers came to the conclusion that “a key component to reducing the stereotypical views of male students towards their female peers would be the greater presence of females in the classroom (or alternatively, a lower presence of males) either as peers or as teachers” (502). In the future, the authors suggest that “future research should consider the potential…effects of all-male STEM learning environments on young males’ views regarding females’ ability, as such contexts [as an all male classroom] could serve to strengthen or at least leave unchallenged boys’ stereotypic beliefs” (502). To put their findings in simpler terms, the authors recommend that the stereotypical perceptions that male students in STEM have towards their female counterparts are challenged or changed so that male students don’t view female students in a stereotypical way.

They focused their study on high school engineering classes, which “represent a relatively new advanced course offering available in approximately only 10% of schools nationwide.” The authors chose engineering classes as they offer an ideal location to study the “stereotypical views of young people and how they change” and also represent the typical ratio of female to male students (493). STEM elective courses are typically comprised of students interested in pursuing a STEM major in college, thus high school engineering courses have relatively fewer female students on average. The study gauged the effects of stereotypical perceptions on both male and female students at the beginning and end of an engineering class, and analyzing how much their perceptions of each other had changed or remained the same. The researchers came to the conclusion that “a key component to reducing the stereotypical views of male students towards their female peers would be the greater presence of females in the classroom (or alternatively, a lower presence of males) either as peers or as teachers” (502). In the future, the authors suggest that “future research should consider the potential…effects of all-male STEM learning environments on young males’ views regarding females’ ability, as such contexts [as an all male classroom] could serve to strengthen or at least leave unchallenged boys’ stereotypic beliefs” (502). To put their findings in simpler terms, the authors recommend that the stereotypical perceptions that male students in STEM have towards their female counterparts are challenged or changed so that male students don’t view female students in a stereotypical way.

As a complement to the research conducted above about teachers and peers in high school classrooms, a report written by psychologist Robert M. Adelman et al. from Arizona State University also argues that female students  “lack similar role models such as peers, teaching assistants, and instructors” in the context of college courses. The researchers conducted a study that examined the effect of a “brief, scalable online intervention” that included a letter from a female role model who normalized concerns about belonging, presented time spent on academics as an investment, and exemplified overcoming challenges on academic performance and persistence (262). These letters include phrases such as “I studied hard for the first test, and felt like I did well on it, but when I got it back, my grade was much lower than I expected” and then immediately go to a phrase after, such as “I remember thinking, ‘Why am I paying a ton of money to go to classes and spending all my time working on them, if I can’t even get good grades?’” However, after using these phrases, the role model would reassure the reader and assure her that they were going through the same struggles and would get through it. The role model served as an example of overcoming adversity to achieve one’s goals and once again normalized challenges at the beginning of college (262). The intervention was implemented in psychology and chemistry courses given through the university. This study was successful, as participants in the intervention group had higher course grades compared to participants in the control group by one fourth of a standard deviation higher grade.

“lack similar role models such as peers, teaching assistants, and instructors” in the context of college courses. The researchers conducted a study that examined the effect of a “brief, scalable online intervention” that included a letter from a female role model who normalized concerns about belonging, presented time spent on academics as an investment, and exemplified overcoming challenges on academic performance and persistence (262). These letters include phrases such as “I studied hard for the first test, and felt like I did well on it, but when I got it back, my grade was much lower than I expected” and then immediately go to a phrase after, such as “I remember thinking, ‘Why am I paying a ton of money to go to classes and spending all my time working on them, if I can’t even get good grades?’” However, after using these phrases, the role model would reassure the reader and assure her that they were going through the same struggles and would get through it. The role model served as an example of overcoming adversity to achieve one’s goals and once again normalized challenges at the beginning of college (262). The intervention was implemented in psychology and chemistry courses given through the university. This study was successful, as participants in the intervention group had higher course grades compared to participants in the control group by one fourth of a standard deviation higher grade.

The marginalization of females in STEM is a major issue in the United States, where there is a deep rooted stereotype that has pushed women out of STEM fields for years. From anxiously studying before a calculus test to feeling my  stomach twist with dread when walking into my programming lab, I have felt the pressure of stereotype threat during my college experience. What I have felt, thankfully, is not because of my experiences at the College of Charleston. Rather, it is from past experiences I have had in school that cause me to react the way I do today towards STEM. I have been lucky enough to have a happy ending surrounding my forays into STEM, but this is still not the case for most female students entering these fields. Schools, from elementary level to college level, need to remove negative perceptions and unfair treatment from classrooms if we want more females to pursue degrees and careers in STEM fields. Fair treatment, safe environments, and the confidence to pursue their interests-instead of struggling under an outdated, oppressive cycle of doubt and regret- are what today’s female students in STEM need to unlock their full potential.

stomach twist with dread when walking into my programming lab, I have felt the pressure of stereotype threat during my college experience. What I have felt, thankfully, is not because of my experiences at the College of Charleston. Rather, it is from past experiences I have had in school that cause me to react the way I do today towards STEM. I have been lucky enough to have a happy ending surrounding my forays into STEM, but this is still not the case for most female students entering these fields. Schools, from elementary level to college level, need to remove negative perceptions and unfair treatment from classrooms if we want more females to pursue degrees and careers in STEM fields. Fair treatment, safe environments, and the confidence to pursue their interests-instead of struggling under an outdated, oppressive cycle of doubt and regret- are what today’s female students in STEM need to unlock their full potential.

Works Cited

Adelman, Robert Mark; Bodford, Jessica E.; Graudejus, Oliver; Hermann, Sarah D.; Kwan, Virginia S. Y.; Okun, Morris A. “The Effects of a Female Role Model on Academic Performance and Persistence of Women in STEM courses.” Basic and Applied Social Psychology, vol. 38, no. 5, 2016, pp. 258-268.

Appel, Markus; Aronson, Joshua; Kronberger, Nicole. “ Stereotype threat impairs ability building: Effects on test preparation among women in science and technology.” European Journal of Social Psychology, vol. 41, no. 7, 2011, pp. 904-913.

Brown, Ryan; Clark, Aaron; DeLuca, Bill; Ernst, Jeremy; Kelly, Daniel. “Engaging females in STEM: Despite students’ actual abilities in STEM, their self-perceptions can be the ultimate deciding factor in what courses they choose to pursue.” Technology and Engineering Teacher, Nov. 2017, pp 29+.

Buontempo, Jenny; Moore, Chelsea; Riegle-Crumb, Catherine. “Shifting STEM Stereotypes? Considering the Role of Peer and Teacher Gender.” Journal of Research on Adolescence, vol. 27, no. 3, 2017, pp. 492-505.

Cooper-White, Macrina. “These Stories Will Help You Understand Why It Can Be Hard To Be A Woman In Science.” Huffington Post, 6 Oct. 2014, huffingtonpost.com/2014/10/06. Accessed 20 Oct. 2018.

Degol, Jessica; Wang, Ming-Te. “Gender Gap in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM): Current Knowledge, Implications for Practice, Policy, and Future Directions.” Educational Psychology Review, vol. 29, no. 1, 2017, pp. 119-140.

Noonan, Ryan. “Women in STEM: 2017 Update.” Department of Commerce, 3 Jan. 2018, www.commerce.gov/news/fact-sheets/2017/11/women-stem-2017-update.

Weber, Katherine. “ Gender differences in interest, perceived personal capacity, and participation in STEM-related activities.” Journal of Technology Education, vol. 24, no. 1, 2012, pp. 18-30

“Women in STEM: stories from MIT students.” Times Higher Education, 9 Mar. 2017, timeshighereducation.com/student/blogs/women-stem-stories-mit-students#survey-answer. Accessed 20 Oct. 2018.

No comments yet.