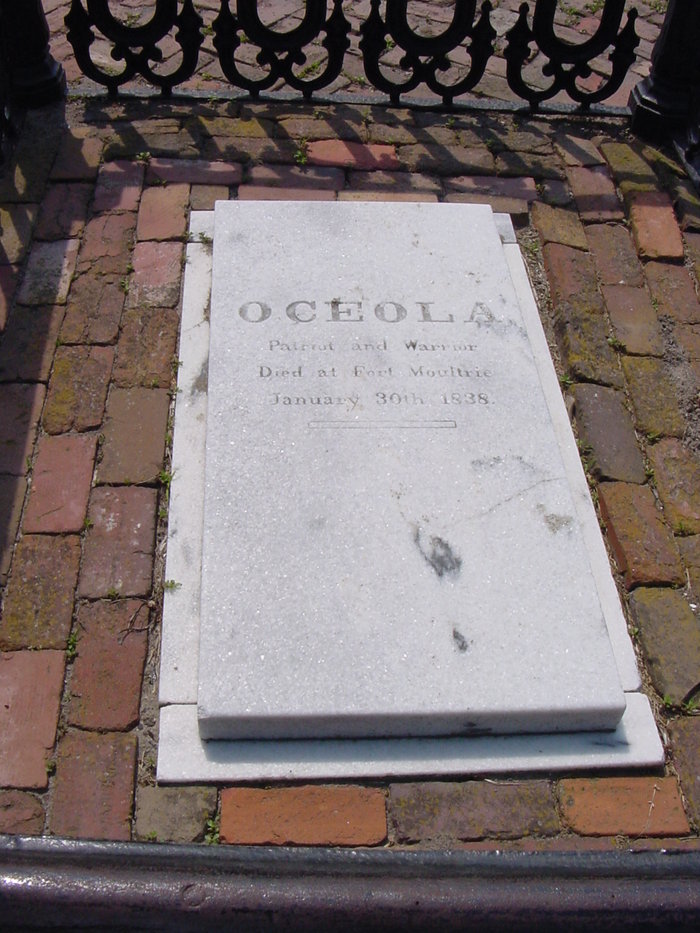

I grew up attending mass at Stella Maris, the small Catholic cathedral on the west end of Sullivan’s Island that is directly across the street from Fort Moultrie. Consequently, I also grew up running around the grounds of Fort Moultrie after mass let out, ducking in and out of the dank brick rooms with my sisters, too young to really care or be aware of what the fort represented–civil war, death, enslavement, imprisonment. As I got older and took field trips to Fort Moultrie and bothered to read the plaques scattered on the grounds that explained its history, I realized how much history I was standing in the center of. This fort had witnessed the beginning of America, whose unfolding was infinitely inspiring and essential to Whitman, and had also been part of attempts to break apart the new and strange country. It had held many types of prisoners as part of its attempt to protect and define America. One of these prisoners was Osceola, a Native American who led the rebellion of the Seminole against the United States’ greedy, inhumane attempts to displace Native people from their land. He was a brief stop on a guided tour: I can recall standing outside of the small black fence that surrounds his grave and peering at the name, “Oceola,” carved in big letters, wondering how a Native American fit into the picture of Fort Moultrie I had in my head, which was populated by white confederate (or American) soldiers.

Osceola’s grave at Fort Moultrie, Sullivan’s Island, SC

Reading Whitman’s poem “Osceola” inspired me to look further into the namesake figure of the poem, which brought my childhood curiosity about this figure into full circle. I learned about Osceola’s role as a leader in the Seminole War, wherein the government of the United States violently forced the Seminole from their land in order to possess it for themselves (“The Seminole Wars”). Native Americans were often tricked or forced into moving from their native lands by the United States government, who did not recognize their autonomy nor their antecedence. Whitman, though he clearly had much respect and admiration for Osceola and Native Americans, tends towards exoticizing their culture in his poems. In “Osceola,” Whitman lays a glossy sheen over the death of a Native American who dies as a prisoner of the US government. So often in our cultural discourse, the terrible treatment of Native Americans at the hands of the government is glossed over in the same way: Native Americans become one stop on a tour, like Osceola was for me; their culture is romanticized while the truth of their struggle and significance is not readily available. For this reason, I thought to write a poem that recognizes the hundreds of thousands of other Native Americans who died at the hands of American imperialism. I based my poem on Whitman’s “Osceola.” It is not meant to compete with Whitman’s poem; rather, to add to the conversation it starts.

Americans

When his hour for death had come–

(And his, and hers, and theirs,)

He slowly curled over his empty stomach,

(Not fed in weeks, his land ravaged by soldiers and having nothing to offer him),

Tried to rise from his bed but could not,

Fix’d his look on the distant horizon,

Then lay down and rested forever.

When her hour for death had come,

She peer’d down at her own red paint coloring her stomach, her leg,

The wound a hole left by a stranger (his visions of rich crop land and American expansion were held before him,)

Felt herself emptying into the soil,

And drew in a breath–the last.

When their hour for death had come,

They rose together, half-sitting, stone-faced;

Gave in silence their extended hands to one another

As they looked upon the strange land before them–

The soil unfamiliar, the wind unforgiving;

Their hearts sank faintly low to the floor

Knowing this was not their true home.

(And here a line left in memory of each of their names and deaths: hundreds of thousands of Native Americans displaced and killed in the name of America.)

I tried to imitate the cadence of “Osceola” by employing multiple commas and dashes like Whitman does. I think this gives almost a sense of urgency as the reader is encouraged to continue through the poem’s hard subject matter. I used some phrases and lines from “Osceola” verbatim, because I want it to be clear that my poem is meant as an expansion of his. I want to retain the sense of respect that Whitman shows for Osceola. At the same time, my poem includes more graphic imagery because I want to illuminate the atrocities that Native Americans suffered–Whitman, on the other hand, writes a peaceful death for Osceola. Certainly this could be an accurate portrayal of how Osceola himself actually died, but Whitman’s poem ignores the larger context of his death–that he was fighting for independence and life for his tribe, not glory for himself.

References:

https://www.seminolenationmuseum.org/history/seminole-nation/the-seminole-wars/

https://www.nps.gov/fosu/learn/historyculture/osceola.htm

Rae, I really liked how you drew upon your childhood experiences, and were able to revisit them and add more meaning through Whitmans work. I think you did a great job with the poem. The point you made about Whitman sugarcoating the experience of the seminole war and the death of Osceola is really apparent and I think you did a good job at rewriting the experience with more authenticity. I also enjoyed reading about your experience as a child running around Fort Moltrie after church. It was innocent as sweet, but also makes a huge point about how history is right underfur feet and so often disregarded when it shouldn’t be, a relateable realization that you came to in retrospect.

This is a really superb re-casting of Whitman’s poem, and your set-up itself offers a great critical overview of Whitman’s poem and its blend of both respect and condescension, with a heavy dose of romanticization. I also appreciate how you situate this poem autobiographically, comparing the glancing attention often paid such figures in the context of grander memorials that tend to take up more physical and imaginative space in the myth of America.

One thing that particularly struck me about your poem was how the Native American presence does not feel at home, or feels their home is different, transformed, and obliterated. Whitman offers elegies to the Native American presence, but they are lost from his world; in your poem, you show them tragically lost from their own world. It’s an interesting twists, and it certainly stood out here.