The contextual readings for this week brilliantly provided an overlapping picture of what many of our poets for the week were all about, from their manifestos on society to their hard and fast but also accommodating rules for poetry. I do not know, however, if in any one or a number of the readings, was there mention of Gertrude Stein and her relationship with Picasso in any fashion other than Picasso was a frequent visitor to Stein’s salon. While I do remember reading and/or discussing Stein and Picasso, I got a very strong sense of Picasso in “If I Told Him A Completed Portrait of Picasso.” My first reaction was that the poem resembled, in verbal form, something like “Guernica.” All of the creatures and people in Picasso’s painting are clearly moving in one direction, and while their forms are recognizable, they are twisted and disproportionate; I felt the same thing was present in Stein’s poem. Because of the form of much poetry in which the words literally begin after the title and end some amount of lines later (as opposed to visual poetry, in which the lines could be located anywhere), I felt that Stein was moving inevitably in a single direction, like the figures in “Guernica,” but the massive amounts of repetition, of disintegrating and reorganizing the syntax of her lines, parallels the modified forms and lines of Picasso’s painting.

“Guernica” Pablo Picasso 1937

I found, to my chagrin, that “Guernica” was created over a decade after Stein’s poem, but found the connection between the artist and the poet was present and strong. In the February 1925 issue of Poetry, Jean Catel writes: “The aim of the symbolic poets had been to get rid of whatever sentimentality related us to the scientific world, to plunge the reader into the stream of consciousness, to use a phrase of a then popular system of philosophy. But in this stream poets and readers found chaos-life is not art, continuity is not poetry” (269). While I do not think that Stein falls under the label of “symbolic poet,” especially because Catel was writing about certain French poets in particular, I think there is something to attributing Stein’s writing to a kind of stream of consciousness, one in which the speaker does not move lithely from image to image but instead seems to be having a sort of reluctant argument on how she would talk to Picasso about a self-portrait of him she had done (assuming the speaker is addressing the “he” as Picasso) or perhaps how she would describe Picasso’s portrait of himself or of the speaker, since we know Picasso painted Stein.

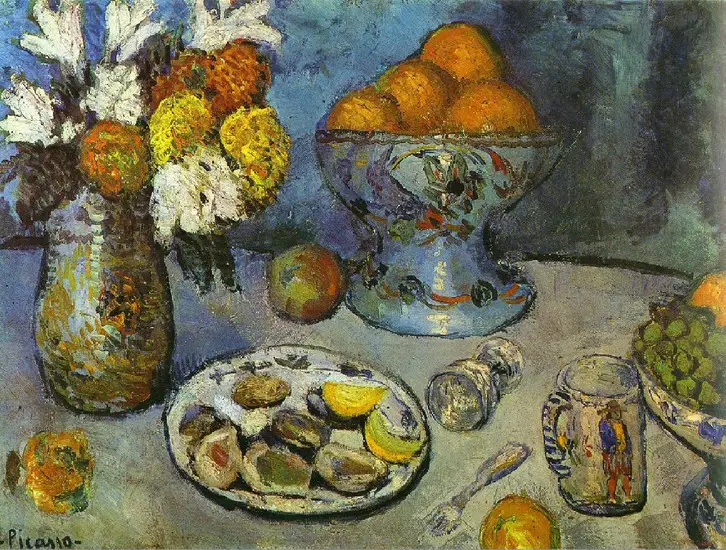

Perhaps more substantial, Jamie Hilder quotes Stein herself in her article linking Stein and Picasso: “In 1938, Gertrude Stein published Picasso, a book which is part biography and part criticism of Pablo Picasso’s work and time. In it Stein claims ‘I was alone at [the] time in understanding him, perhaps because I was expressing the same thing in literature'” (67). While Hilder goes on to make the argument that Stein’s similarities to Picasso’s work extend far beyond the form, my initial impression was of that of form. I have (hopefully) embedded several of Picasso’s works which I think can draw parallels to Stein’s poetry.

“Plaster head and arm” Pablo Picasso 1925

“Still Life (Dessert)” Pablo Picasso 1901

Works Cited

Catel, Jean. “As It Is in Paris.” Poetry, vol. 25, no. 5, 1925, pp. 268-273. JSTOR.

Hilder, Jamie. “‘After All One Must Know More Than One Sees And One Does Not See A Cube In Its Entirety’: Gertrude Stein and Picasso And Cubism.” Critical Survey, vol. 17, no. 3, 2005, pp. 66-84. MLA International Bibliography.

Stein, Gertrude. “If I Told Him A Completed Portrait of Picasso.” The Oxford Book of American Poetry, edited by David Lehman, Oxford University Press, 2006, 242-244.

BONUS

Stein’s writing also reminded me of this comedian who, though he communicates in a very nonstandard way, always gets the point across:

Bruce, I agree with your assertion that Stein’s work has the sense of a “stream of conscious” approach. It’s as though she displays her interior monologue to her readers – the exacting over how to say something precisely. The language she uses, especially through the repetition of monosyllabic words, creates such vibrancy on the page that the rhythm of what she’s written has stayed with me long after reading the work itself. Rereading this poem just now gave me the sense of painting a portrait. For anyone who has painted – and especially with oil or acrylics – there is the color blocking, the refinement, and the details of going over and over and over the piece again. This is the sense of process Stein achieves with her poetry – the chiseling of images with rearrangement of words to produce a crisp picture to readers. What did the Mina Loy poem say about her? “Curie/of the laboratory/of vocabulary” (276). Beautifully stated.