“Nature Hates Calculators”: Emerson and the Essay

Anthony Garruzzo

There is no denying the humility behind the name essay, which originally simply meant an attempt. The history of the term begins with Montaigne, who, as a moderate skeptic, would wade into subjects with wariness and self-doubt, always willing to admit the narrowness of his own perspective. Being so conscious of his own limitations, Montaigne would not even aim to be fully systematic in his handling of a topic, rather only venturing an “attempt” to suit his thoughts to the subject, with little method or direction. While this looseness of form and lack of rigor do still color the essay today, over the years it matured as a genre and, through the work of many noted practitioners, distinguished itself from a mere haphazard “attempt.” Still, such conventions as a conversational tone and an explorative rather than argumentative mood remain hallmarks of the genre and imply a disinclination to meticulous structuring. Form, it may be said, is traded for tone; structure for freedom. Though overly simplistic, this perspective on the essay does not seriously distort the genre; much of the appeal of the essay in fact derives from its negative relationship with other genres, which, unlike it, compel the writer to torture her ideas into the shape that the genre prescribes.

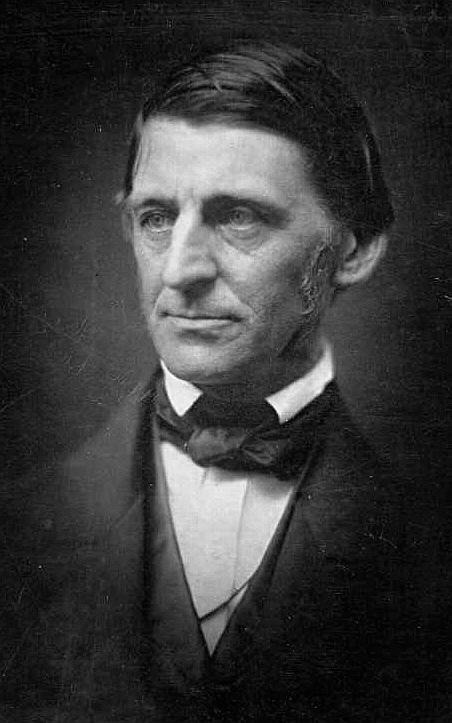

One of the most famous essayists, Ralph Waldo Emerson, seems to perpetuate the tradition of the tangential, amorphous essay. His works read like improvisations on a riff, to adopt a jazz metaphor, seemingly stitched together of thoughts plucked without design from his journals. However, this interpretation overlooks how Emerson’s participation in the essay genre disguises a deliberate formal aesthetic. Theorists of Emerson’s prose have noted that his essays are carefully constructed so as to critique the way that concepts come to be determined by different systems of thought, whether they be languages, cultures, mythologies, or philosophies. By connecting this insight with the traditional essay’s condemning attitude towards the systematization of ideas, I argue that a clearer understanding of the subversiveness of Emerson’s prose emerges. That is to say, Emerson’s method of subversion becomes much more transparent when understood in the context of the essay’s rejection of systems of ideas as inadequate constructs of meaning. However, by way of contrast, the essay traditionally responds to this rejection by relocating meaning in a modest, structureless empiricism, testing the viability of concepts by filtering them through the lens of experience. Emerson, on the other hand, does not abandon the usual systems of thought but, instead, elaborately engages with them and subtly demonstrates their inadequacy for ordering all of the concepts that they have gathered together. Understanding this clarifies other theories on the form of Emerson’s essays as well as how the essay as a genre informs Emerson’s writings.

To establish my argument, I begin by exploring Douglas Atkins’s description of the essay genre as being defined by its rejection of systematic thought in favor of locating meaning in the self and experience. I discuss how Emerson also rejects systematic thought but, gesturing to other scholars, I contend that he rejects it not by abandoning it and turning to experience, but rather by critiquing its inadequacy and engaging with its very structure. First, I discuss how Stanley Cavell interprets Emerson to be attacking the Kantian conception of experience on the basis that it necessitates choosing between objectivism and subjectivism, though Emerson does not think there need be any choice between them. He thinks any system of thought that forces such a choice is structurally flawed. Thus, Emerson’s approach is critical of the way ideas are configured into systems, which matches Julie Ellison’s treatment of his style as “sublime analysis.” She argues that Emerson recognized the shared basis behind all mythologies, or systems of thought, and so critically engaged with the way their shared foundations are cosmetically differentiated. I then explore Kelly Dean Jolley’s explanation of how Emerson accomplishes this critical engagement at the level of the sentence, before demonstrating myself how this method leads to Emerson’s critique of the concept of experience through his use of the word “excess” in the essay “Experience.”

//

Now we might be tempted to ask: what theory of experience emerges from this? This would be the wrong question, however, since, as Emerson says himself:

I know better than to claim any completeness for my picture. I am a fragment, and this is a fragment of me. I can very confidently announce one or another law, which throws itself into relief and form, but I am too young yet by some ages to compile a code. (288-289)

That is to say, this does not constitute a theory of experience, but only a critique of experience as it is systematized. Here, again, is the note of the essayist, not replacing systems but rather reacting against them. It is the essayist’s attitude that is behind Emerson, but not her methods. Interestingly, in “Experience,” Emerson converges with the traditional essayist by mounting his rebellion against the systematization of ideas through reference to experience. Yet he does not do this by relying on experience as a filter for meaning, but rather by dissecting and critiquing experience as an idea itself. To discover the full contours of this critique there still remains the task of assessing the essay’s use of the many signs besides excess, and to sharpen understanding of Emerson’s link to the traditional essayist this critique must be related to the essayist’s perhaps naive hope that experience can of its own authority sustain meaning.

No comments yet.