by Brandon Eichelberg

Since its release in 2014, critics and fans alike have hailed season one of HBO’s True Detective as some of the best television ever made. Following two major figures, Rustin “Rust” Cohle (Matthew McConaughey) and Martin “Marty” Hart (Woody Harrelson), the season displays disgusting, riveting, and confusing twists with each episode (there are only 8!). Taking place over a seventeen-year period (from 1995 to 2012), detectives Cohle and Hart attempt to solve a string of serial murders which only grows more grotesque and horrifying as the show progresses.

With this piece, I have aimed to not reveal any spoilers, though, of course, they will inevitably sneak through. So, with that being said, be forewarned.

Each time I (re)watch the first season (there are two other seasons, though, for the purpose of brevity and quality, I refrain from mentioning those two mediocre pieces of television any further), I am always amazed by the Gothicism throughout it. The show lies on the cusp of horror, though, in my opinion, I would not go as far as to call it horror. Because of this fault in the liminality of the genre, I’ll refer to this show as Gothic, specifically Southern Gothic.

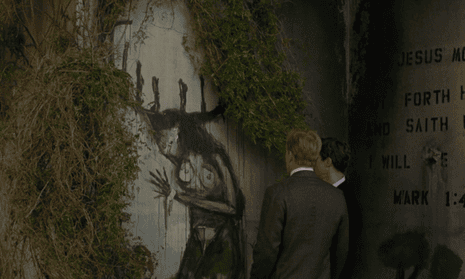

Taking place in the deep south of Louisiana, the cinematography perfectly captures this Southern Gothicism. With its live oaks and murky marshes and abandoned churches, the mini-series highlights the formal setting of a Southern Gothic piece. The one Gothic element that the show does not include throughout, however, is a central decrepit house or manor. There is no central house throughout the whole season. Though, some episodes do focus on a central building, such as in the fifth and eighth episodes, “The Secret Fate of All Life” and “Form and Void.”

Besides the setting, the mini-series displays Gothic elements through its psychological uncertainty. We are first introduced to Cohle under mysterious pretenses. He’s an outsider to the rest of the homicide detectives at the Louisiana State Police Department. He takes notes on a large “taxman” pad, keeps to himself, and says strange esoteric things. One of the strangest is, “In eternity, where there is no time, nothing can grow. Nothing can become. Nothing changes. So death created time to grow the things that it would kill, and you are reborn but into the same life that you’ve always been born into” (“The Secret Fate of All Life”).

Like, what the hell man – just solve the case. Right? Wrong!

This eerie, even horrifying, image – belief? curse? purgatory? – reflects both Epicurean metaphysics and nihilism, two interestingly paired philosophical schools of thought – perhaps pulling from Nietzsche. Cohle’s ambiguity coupled with his intelligence leads the audience to question his motivation. This ambiguous drive that inhabits Cohle reminds me of the ambiguity found within William Faulkner’s Sanctuary. Within this novel, motivations are not necessarily made clear unless one truly unravels them – and even then, they still may be blurred.

We see a very similar ambiguity in the character of Rust Cohle. Why is he chasing this serial killer? Why does he care so much? Well, yes, it is his job – but it’s more than just a job for him. It’s a duty. But why?

We soon find out that Cohle has a dead daughter – and the serial murders all include young women and children. Furthermore, he struggles with alcoholism. As the jumping of time between the three eras distorts the storyline, we see Cohle as he sinks deeper into alcoholism, further associating the audience with his disturbed mental state. We are confused and that’s the point. The more we find out about Cohle, the more we found out that there is more to find out.

While the story revolves around a 17+ year chase for a serial killer, it is really about the relationship between the two main characters. Cohle and Hart simultaneously chase the evil causing the murders while confronting the evil within themselves. They confuse themselves and threaten the case. They confuse the external with the internal, the internal with the external.

Much like Cohle, Hart has his own closet of hidden skeletons. He fights to keep the case just as strongly as Cohle does. Though, much like Cohle, his motives are questionable. We quickly find out that Hart cheats on his wife with a young woman. This eventually turns into multiple young women as the show progress. Hart also has two young daughters. The show intermingles these two aspects of Hart and suggests a weird pseudo-incestuous motive that drives him to find the serial killer(s). This, too, reminds me of Sanctuary and Benbow’s strange relationship with his stepdaughter and Temple’s horrifying situation with her father and brothers.

The show, in my opinion, is a masterpiece of modern television. It’s too long to be a film, it’s too short to be a whole series, and the creators knew that from the beginning. I’ve watched the mini-series about four – maybe five – times since its release, usually while sharing it with a friend or family member. It’s amazing. I highly recommend it, though, it is an intense show, so, as before, be forewarned.

Hi Brandon!

Some very nice philosophizing here on the intricacies of True Detective, a show that I’ve never watched but from your description reminds me somewhat of Netflix’s Mindhunter.

Shows like this I feel are almost always inherently Gothic – they would almost be procedural, if not for the larger focus on overarching plots and developments throughout. Most especially with the moral ambiguity you discussed, this show seems very focused on the darkness of humanity and its demons, exploring psychological elements surrounding Cohle and Hart. The locale is important, but mostly serves to contain and ground the narrative that could otherwise get lost when focusing on the morality of Cohle and Hart, especially over almost two decades.

Upon further research into the show, just to get a further vibe of it beyond discussion of the Gothic, I was surprised that it’s simply an anthology show. No wonder only the first season deems mention! In my experience, anthologies are very hard to perfect and hit their mark every time, especially when it seems the creative team captured lightning with their first try.

Some of my favorite Gothic media are just as self-contained as True Detective’s first season, not overstaying their welcome but like you mentioned at the end – they knew their story and how much time it needed. I find that a lot of Gothic media fits that generalization, as very rarely do moments feel out-of-place or wasted; everything has its place and role in the narrative whether for the entire length or just a brief moment. A sign of a well-written story is recognizing that and using it to the benefit of the story – which True Detective seems to accomplish in droves.