Hayden Anhedönia is a singer-songwriter from Georgia who has been associated largely with her exploration of the Southern Gothic aesthetic, most prominently in her 2022 album, Preacher’s Daughter, released under the stage name Ethel Cain. The narrative of the album centers around a young runaway who finds herself in the hands of a cannibalistic psychopath but also explores the euphoria surrounding her newfound unabridged freedom in the foreground of the rural south. The sound of the album oscillates between melancholy and eerie as she sets the scene of the album in Shady Grove, Alabama. The album evokes the atmosphere of a decaying South, plagued with dark secrets and haunted by the ghosts of the past.

One of the defining features of the southern gothic genre is its focus on the macabre and grotesque. Preacher’s Daughter permeates themes of death, betrayal, and madness through dark, low vocals that echo and lyrics that portray murder and its sinister invocations. The opening track, “Family Tree(Intro)” features Ethel’s voice echoing through the dark halls of a church. She sings, “Swinging by my neck from the family tree, he’ll laugh and say, ‘You know I raised you better than this’, then leave me hanging so they all can laugh at me”. The lyrics suggest a character haunted by past misdeeds and abuse, finding herself unable to escape the cycle of guilt and shame and used as an emblem of this abuse.

In addition to Preacher’s Daughter’s portrayal of the Southern gothic through deeply religious themes and a continuous narrative, other singles and unreleased songs of Cain’s continue to develop this aesthetic. Embodied by the recurring image of ghosts and otherworldly apparitions, in “Crush,” Cain sings, “There’s a shadow in the doorway, and I can’t tell if it’s you or a ghost.” The ambiguity of this line is typical of the genre, where the between reality and imagination is blurred into fantasy. In “Fall of the House of Usher” by Edgar Allen Poe, this space between illusion and reality – or rather, the fine line between madness and sanity – is expressed through the cheerless, melancholic appearance of the House of Usher. Both “Fall of the House of Usher” and “Crush” seem to suggest that the gothic nature of haunted houses is deeply rooted in the psychology of the narrator. The use of supernatural elements serves to heighten the sense of unease and dread that permeates the album.

The Southern Gothic aesthetic is also characterized by its emphasis on decaying environments. Cain’s lyrics describe crumbling buildings, rusted fences, and overgrown gardens in “Michelle Pfeiffer” where Cain sings, “The garden’s overgrown and the fence is rusted through, there’s a hole in the roof and the windows are all blue.” This imagery evokes the decay and decline of the South, as well as the sense of isolation and abandonment that is often associated with the genre through its descriptions of dead or barren land. Similarly in the second to last track of Preacher’s Daughter, Cain opens the song by describing a common sight in the southern U.S., where the sun can bleach dead insects stuck to windshields or windows, creating a macabre and unsettling image of death. Cain sings, “Sun bleached flies sitting in the windowsill, waiting for the day they escape”, before reaching the line “God loves you, but not enough to save you”. This line suggests the inner religious turmoil of the speaker and examines the contradictory relationship God seems to have with his worshippers. Cain is positing that God doesn’t provide sanctity for her, but only doubt. She reaches the conclusion that “I always knew that in the end no one was coming to save me,” and retires her faith.

In addition to its focus on decay and the supernatural, the Southern gothic genre often explores issues of race and class. Cain’s lyrics often examine the experience of growing up in a deeply religious and conservative environment. In “Take You With Me,” Cain sings, “In the church we raised our hands, but the preacher didn’t understand that we were lost and looking for love.” The tension between the strict morality of the church and the complexity of human desire is a theme that is explored throughout the album. It also evokes a sense of abandonment and isolation, as Cain finds herself in an emotional deficit and looks to God as a form of sanctity.

Ethel Cain’s debut album, Preacher’s Daughter, is a stunning example of the southern gothic aesthetic. With its focus on the macabre, supernatural, and decayed environments, as well as its examination of issues of race, class, and gender, the album aligns with the key themes of the genre. Cain’s haunting lyrics and eerie soundscapes evoke the atmosphere of a South haunted by its past, and the album stands as a testament to the power and enduring appeal of southern gothic.

One of the most iconic pieces within the Jack the Ripper Stalks His Victims collection was the Pink Silk Satin Coat with thorn patterned lines and encapsulated human hair. His idea of lining a majority of his collection with human hair was due to the Victorian Era when sex workers would sell their locks of hair to be given to peoples lovers. McQueen using his own locks of hair to finish the collection. His collection fits a gothic theme due to his inspiration being Victorian Gothic mixed with horror and romance. A majority of his collections had life and death styles with a sinister aspect creating a strong gothic theme. Every fashion show representing a new collection of his is told with a story.

One of the most iconic pieces within the Jack the Ripper Stalks His Victims collection was the Pink Silk Satin Coat with thorn patterned lines and encapsulated human hair. His idea of lining a majority of his collection with human hair was due to the Victorian Era when sex workers would sell their locks of hair to be given to peoples lovers. McQueen using his own locks of hair to finish the collection. His collection fits a gothic theme due to his inspiration being Victorian Gothic mixed with horror and romance. A majority of his collections had life and death styles with a sinister aspect creating a strong gothic theme. Every fashion show representing a new collection of his is told with a story.

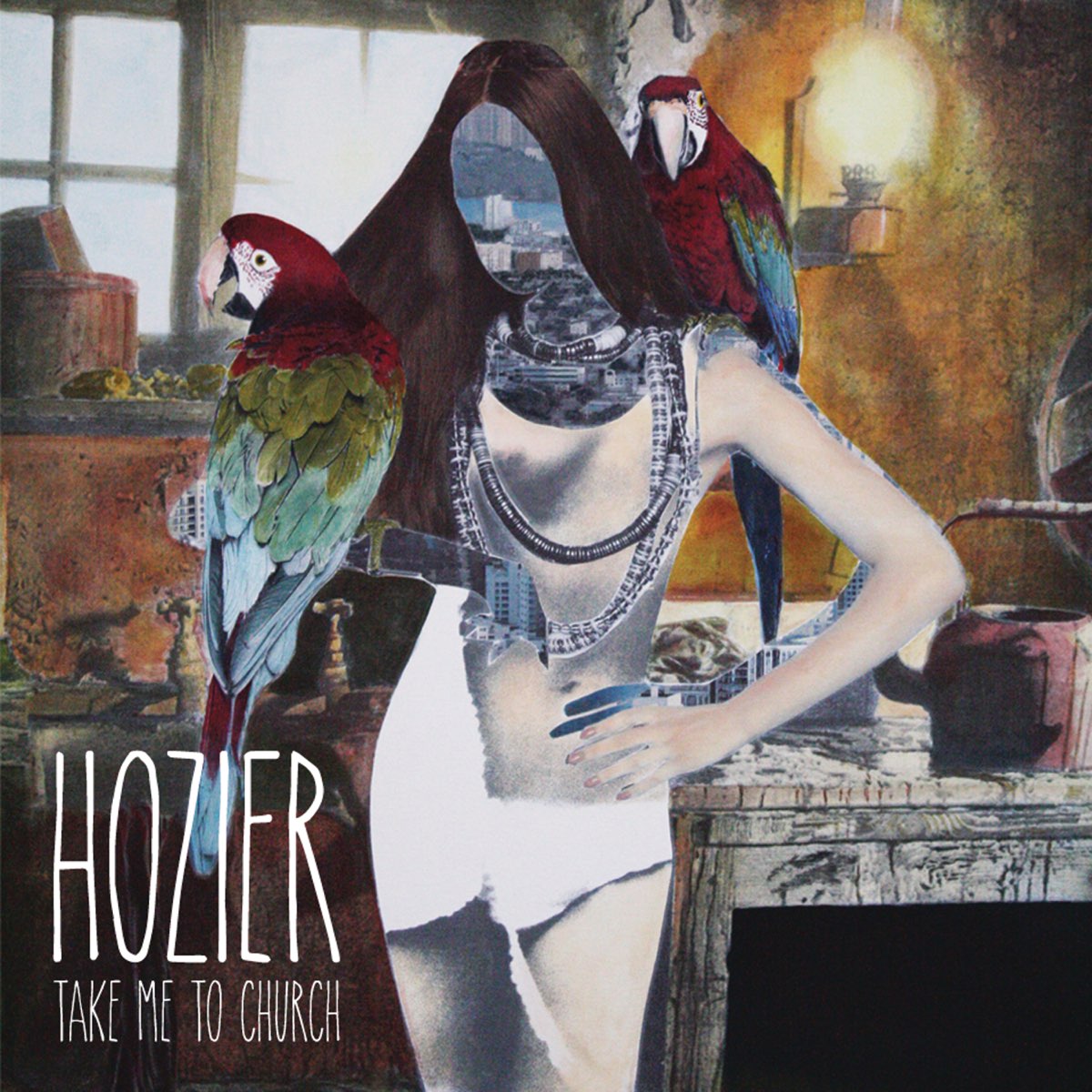

accredits his inspiration to American blues and jazz singers like Nina Simone and John Lee Hooker. For this reason, Hozier is often associated with the Southern Gothic. Many of his songs explore the supernatural and the horrific, and many emphasize a particularly sinister side of religion. This is best exemplified through Hozier’s 2014 debut self-titled album. I loved this album when it first came out, and I was really excited to revisit it with a well-informed Gothic lens.

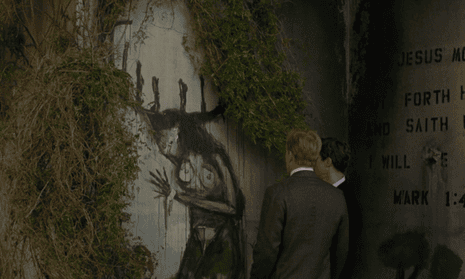

accredits his inspiration to American blues and jazz singers like Nina Simone and John Lee Hooker. For this reason, Hozier is often associated with the Southern Gothic. Many of his songs explore the supernatural and the horrific, and many emphasize a particularly sinister side of religion. This is best exemplified through Hozier’s 2014 debut self-titled album. I loved this album when it first came out, and I was really excited to revisit it with a well-informed Gothic lens. This song reminded me a lot of “Circumstance.” In that story, a woman is attacked by a creature. At times, it seems that the animal is attempting to rape the woman, conflating the feral instincts of animals with the darker and animalistic instincts of man. Hozier draws upon the same idea in his song: it is ultimately impossible to tell if the speaker is animal or human, only that it is intensely drawn to the woman. In both texts, home represents protection and safety. In “Circumstance,” the woman is attacked while venturing outside of her home and is eventually saved by representations of her home life—her husband and child. In “It Will Come Back,” the creature only ever exists outside of the home. Crossing that boundary and allowing it inside will harm the woman by making it impossible to get rid of.

This song reminded me a lot of “Circumstance.” In that story, a woman is attacked by a creature. At times, it seems that the animal is attempting to rape the woman, conflating the feral instincts of animals with the darker and animalistic instincts of man. Hozier draws upon the same idea in his song: it is ultimately impossible to tell if the speaker is animal or human, only that it is intensely drawn to the woman. In both texts, home represents protection and safety. In “Circumstance,” the woman is attacked while venturing outside of her home and is eventually saved by representations of her home life—her husband and child. In “It Will Come Back,” the creature only ever exists outside of the home. Crossing that boundary and allowing it inside will harm the woman by making it impossible to get rid of.

In this look, McQueen uses traditional Victorian clothes for inspiration for the corset. Each stage of mourning in Victorian society had a different dress code, half-mourning was lilac. This lilac corset with black jet beading, also consistent with mourning, was paired with a patchwork denim maxi skirt in all of its 90’s glamor. While a collar that is reminiscent of gothic spires encloses the model in a corseted prison on top, the bottom half of the look seems as though it could have pulled right off of the most current 90s it-girl.

In this look, McQueen uses traditional Victorian clothes for inspiration for the corset. Each stage of mourning in Victorian society had a different dress code, half-mourning was lilac. This lilac corset with black jet beading, also consistent with mourning, was paired with a patchwork denim maxi skirt in all of its 90’s glamor. While a collar that is reminiscent of gothic spires encloses the model in a corseted prison on top, the bottom half of the look seems as though it could have pulled right off of the most current 90s it-girl.

McQueen borrowed from photographer Joel Witkins for this crucifixion mask first seen in Witkins self-portrait taken in 1984. The mask accompanies many different looks and has been read in a variety of different ways. Resurrection, ego, and the ‘mask’ of religion are a few ways this can be interpreted and there is probably truth in all of them. After all, McQueen loved collapsing two contradictory ideas, lifestyles, opinions, etc., into a single garment.

McQueen borrowed from photographer Joel Witkins for this crucifixion mask first seen in Witkins self-portrait taken in 1984. The mask accompanies many different looks and has been read in a variety of different ways. Resurrection, ego, and the ‘mask’ of religion are a few ways this can be interpreted and there is probably truth in all of them. After all, McQueen loved collapsing two contradictory ideas, lifestyles, opinions, etc., into a single garment.