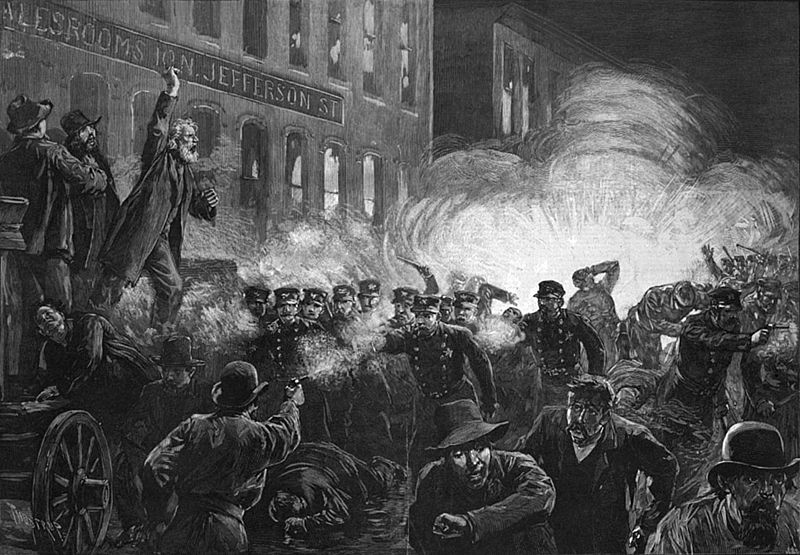

This podcast interview with Timothy Messer-Kruse, author of The Trial of the Haymarket Anarchists: Terrorism and Justice in the Gilded Age offers a new perspective on the Haymarket bombing of May 4, 1886. Based on a careful review of the little-researched trial transcripts and other evidence, he comes to conclusions that undermine some of the long-held beliefs about the event and the trial that followed.

This podcast interview with Timothy Messer-Kruse, author of The Trial of the Haymarket Anarchists: Terrorism and Justice in the Gilded Age offers a new perspective on the Haymarket bombing of May 4, 1886. Based on a careful review of the little-researched trial transcripts and other evidence, he comes to conclusions that undermine some of the long-held beliefs about the event and the trial that followed.

Pervasive and popular interpretations of the “affair,” as it is often called, include the idea that the eight who were tried were tried solely because of their politics, and not because of their actions, since there was no evidence of a bomb plot. Messer-Kruse argues that “there was indeed a conspiracy to throw a bomb on May 4th”; it was planned and some of the individuals involved in the plot were on trial. The anarchists were looking at the Haymarket event as an opportunity to spark an insurrection, in the mold of John Brown. As was slavery for Brown, industrial capitalism for the anarchists was an evil system and violence was the appropriate response.

Another popular interpretation is that the trial was “uniquely unfair.” M-K says that in the context of the time, the trial was not unusual or unfair by comparison to other trials, though we clearly an rightly think it illegitimate now. But we have to keep in mind, M-K says, that standards and processes of criminal procedure that now form the core of how we think about the justice system were being formed at the time. In its context, M-K argues, the trial was not unusual.

The Haymarket martyrs, as they have been called, have been inaccurately depicted as moderate trade unionists, 8-hour day supporters, and so forth–generally, as falling in line with incremental reformists. M-K says that these movements — the very essence of incremental, slow organization-driven changes — the anarchists spent their lives fighting against. “These men were revolutionary anarchists. They believed first and foremost in the revolution.” Action was the main thing: propaganda of the deed, as opposed to education. Theory and what to do after the revolution could wait.