“Don’t Call Me an American; I’m a New Yorker”:

Abstract Expressionism in the Contemporary American Metapoetry of the New York School

Grace Elora Vail

_________________

The New York School is made up of poets who drew from abstract expressionist art and themes, recognizable through poets such as Barbara Guest, Frank O’Hara, James Schuyler, Kenneth Koch – those who used rich imagery yet abstract sentences and representations of ideas and situations. These poems can be about many things due to a variety of ideas being presented in a single poem, so at the same time can be about very few things because they lack a centralized theme and resort to abstraction. Since we can never really see into another person’s mind, the true essence of these poems is quite often a mystery to readers or deemed difficult to fully understand. Yet there are far more layers to these poems than that which we are trying to see “underneath” the words on the page. Instead of reading a poem and either “getting it” or not, poetry can be viewed as writers merely inviting readers into their world by using language with different stylistic choices. The different forms this language can take and the eras that contribute to them are what make up varying schools of poetry. The New York School has been called “the last authentic avant garde movement that we have had in American poetry”, categorized by poets who were influenced by abstract thinkers and use obscure descriptions of scenes and feelings that tend to leave it to the reader to find meaning (Lehman 284).

So, what happens when the veil is lifted, and the writing isn’t so abstract? What comes out of poets breaking through the obscurity and saying, “Reader, I’m having trouble expressing myself”? This is known as metapoetry–poems that stem from writers needing a different layer of connection to get their feelings and thoughts across. In short, poems about poems. Their depth, forms, difficulties, failings, and nuances are brought to light in the midst of the usual form and style of a poem. Like a call for help or understanding, these examples are an invitation to the reader, trying to relate feelings and situations in a more direct way than the usual smoke and mirrors characteristic of the New York School.

Metapoetry can be understood along the same lines as Horace’s “Ars Poetica”, a collection of epistles (letters) written in the first century regarding the practice of writing poetry. The term is now used to refer to “poetry about poetry”, or poetry as an art to be practiced. My understanding of this type of self-aware poetry tends to align more with the definition of metapoetry associated with literary criticism and “metacritical” works, specifically that which can be studied as meta or self-aware vs. what is explicitly describing itself as “poetry about poetry”.

While critics such as Mae Losasso and David Lehman recognize the deconstruction and “adversarial character” of the New York School, scholars such as Josh Schneiderman agree that this movement included poets that were actively participating in the mainstream poetry creation of the time (Lehman 284). Schneiderman frankly states: “Far from being indifferent to it, the New York School was founded on both an attack on and a direct engagement with the establishment”, and admits the duality behind a movement often recognized as avant-garde and non-conforming (Schneiderman 350). Not only were they actively participating, but breaking through the poetic “fourth wall” and addressing the reader to communicate often deeper and more intimate confessions. This engagement is noticed within several key writers of the school, most notably James Schuyler and John Ashbery, who have a surprising amount of instances where their poetry breaks through its usual form and addresses the reader. The sometimes ineffectiveness of language is exemplified by this break, and the writer is apparently left with no other option than to reach through the genre and address the reader.

In fact, many poems of this era are quite meta–discussing the relationship between the poet and the words, describing (however abstractly) the distance between meaning and language that is understandable to a reader or a specific person. For a school of poets so concerned with breaking from form, verse, and conventional types of writing, this concern manifested in direct representations of this struggle on the page. This discernment is helpful not just to categorize poets or schools, but to create a closer connection between poets and their practices in order to understand their reasoning. By not focusing on any one style of writing or parameter, they coincidentally created a movement that led to poets specifically returning to form and discussions of writing itself. Therefore by tracing these poems in the context of the author’s works, themes of the era, and rejection of conformity, a better understanding of the New York School’s poetry is created from studying abstract expressionism alongside metapoetry.

This seems almost counterintuitive when considering the New York School, founded with a spirit of “opposition to the status quo,” and its overarching belief that “change is ameliorative, rapid change especially so, that destruction is essential for creation” (Lehman, Schneiderman 284-85). For a school so focused on breaking from conformity, there is a noticeable pattern of poems about expression and poetry itself. What is meant to be based on deconstructionist principles on the surface presents as formally constructed and even plain in practice.

An initial introduction to the New York School can best be represented by the self-proclaimed founder, Frank O’Hara. Originally from Massachusetts, the poet lived and studied in New York, writing poetry that became well known for being based in observation and urbanity. O’Hara wrote “Personism: A Manifesto”, a satirical take on both the idea of literary movements, the essence of his writing style, and the New York School’s inspiration. In essence, he thought poetry should be a relationship between the reader and the poet that is not concrete, but more abstract, where “Abstraction (in poetry, not in painting) involves personal removal by the poet…. to give you a vague idea, one of its [Personism’s] minimal aspects is to address itself to one person. It puts the poem squarely between the poet and the person.” It follows the same logic as an aphorism from Douglas Oliver, who believed that “Each narrowing of what contemporary poetry is supposed to do bears with it an equivalent narrowing in the definition of a human being” (M. Nelson xvii). What O’Hara started with Personism turned into the New York School, gaining notoriety as a group not taking themselves too seriously and experimenting with form and its deconstruction.

The inspiration for this deconstruction of form stemmed, in part, from contemporary art. This relationship is dissected in Maggie Nelson’s book Women, the New York School, and Other Abstractions, where she analyzes the relationships between abstract expressionist painters and poets through a feminist lens. Her introduction provides strong points for the groundwork of an argument against the idea of “true abstraction” and dissects O’Hara’s “Personism” in order to define a more modern, or realistic, understanding of the intention behind abstract poetry. As Nelson sees it, “On the one hand… this ‘true abstraction’ could designate something deeply and truly abstract, with no concrete referent; on the other, it could designate something seemingly abstract that turns out to be ‘true’, that is, real, literal, or materialized” (M. Nelson xviii). More specifically, this deep self-awareness ends up providing an intimate relationship between the poet and the reader due to the conclusion the poet needs to have a sense of removal from the poem for the reader to assign their own meaning.

Abstract expressionism in painting became a key inspiration for the New York poets, despite a lot of originators of the art era doing most of their work in the earlier decades of the 1900s and hailing from places outside of the United States. Wassily Kandinsky was Russian, Paul Klee German and Swiss, and Willem de Kooning from the Netherlands, all of whom are considered revolutionaries of abstract expressionism. Jackson Pollock, however, was from Wyoming, studying art in New York City and creating from the mid 1930s to mid 1950s. Joan Mitchell was also born in America, attending Columbia University and exhibiting at several galleries in New York, though she spent most of her creative years living in Paris. Their paintings consist of indirect and nonobjective forms and shapes, the main goal being self-expression. Take de Kooning’s painting Whose Name Was Writ in Water for example. There are so many different directions the lines and forms can take the painting, a chaotic yet somehow finite scene suggesting turmoil in water.

Willem de Kooning, Whose Name Was Writ in Water, 1975

These feelings and suggestions are reminiscent of poems from writer James Schuyler, where his poems evoke dark feelings and vague realizations, though obscure in the “true” or exact meaning behind his writing.

Well-known abstractionist painter Jackson Pollock created the famous Blue Poles, a large-scale painting formed from a drip painting technique, which Pollock deemed an interactive or “action painting”, characterized by his relationship with the canvas. This painting is perceived as emotionally charged, due to the striking lines that seem to cut through the turmoil represented through the layers of shocking hues.

Jackson Pollock, Blue Poles, 1952

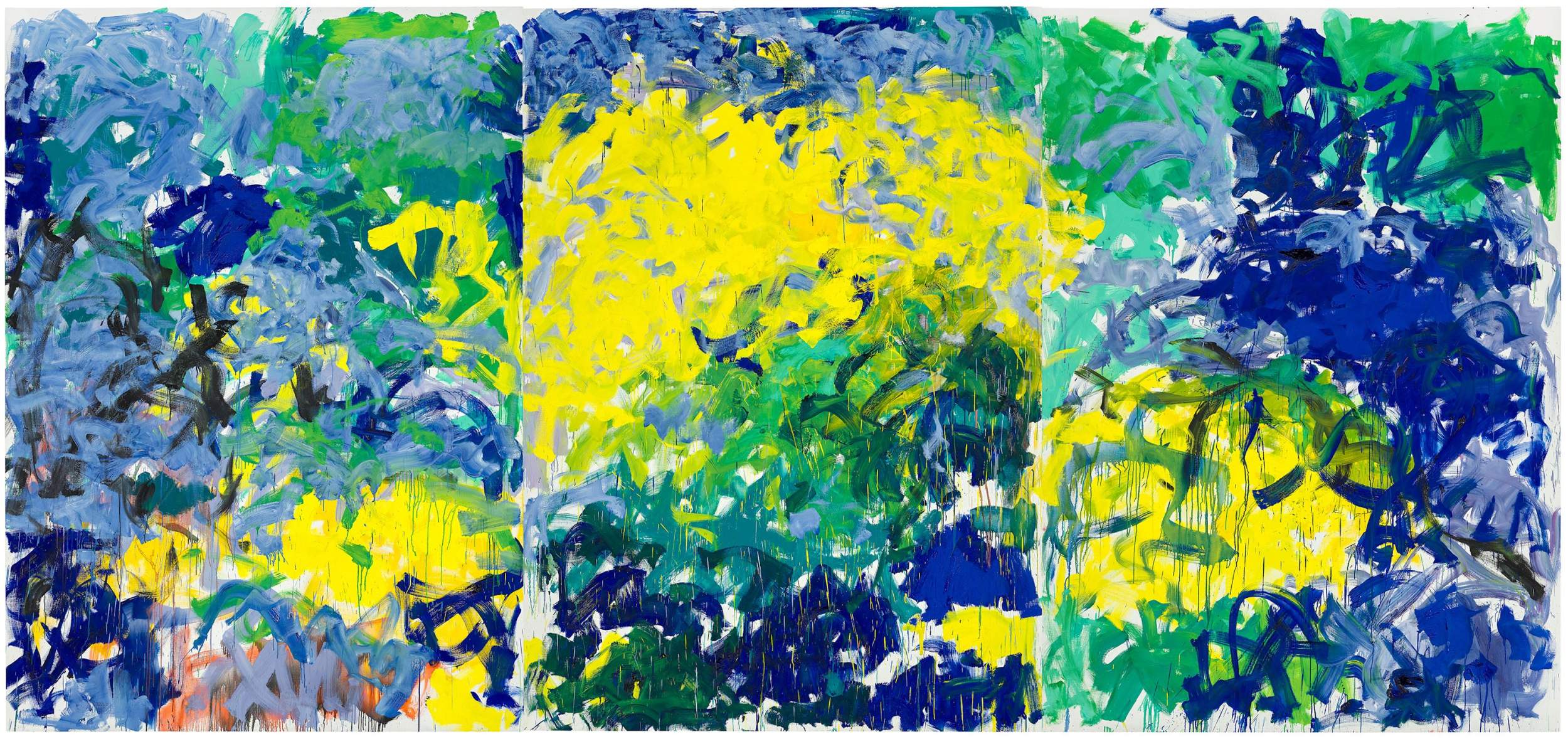

Joan Mitchell’s La Grande Vallée XIV (For a Little While) is arguably less visually abstract compared to Pollock, a striking depiction of flowers morphed from deep hues of blue, yellow, purple, and green elements. Despite the clearer presentation of the subject as flowers, the context, amount, type, and other elements of the painting are still unclear, matching the abstractionist movement’s uncertain characteristics.

Joan Mitchell, La Grande Vallée XIV (For a Little While), 1983

As the above paintings exhibit, this was a very broad art movement that can encompass many types of expression, whether it be a chaotic scene depicting rough water, a group of lines that seem messy, or a painting suggesting some flowers.

As immeasurable as most abstractionist art can seem visually, it is important to note the amount of planning and thought that goes into making something abstract. Paintings can seem spontaneous, but large scale works like those of Mitchell, Pollock, and de Kooning’s took up entire walls and required careful consideration of time, place, purpose, and subject. Not only does the physical space allow room for more creativity, but the lack of definition allows more room for painters to convey several feelings and concepts through their work. This is paramount to my argument challenging the abstract and spontaneous goals of New York School poets, due to there being no such thing as an unintentional or unplanned poem. The measured decision to shy away from a certain theme or message can create the opposite of this intention, and subsequently cause poets to revert back to self-referential metapoetry that is no longer abstract. This is especially true for a writer such as John Ashbery, who described his own process as “… actually deconstructing my poetry in the sense of taking it apart, and the pieces were lying around without any coherent connection” (Losasso 82). As Mae Losasso explores in her book Poetry, Architecture, and the New York School: Something Like a Liveable Space, Ashbery’s writing consisted of “literally taking the language apart and reassembling it in the space of the poem” (Losasso 82). James Schuyler implements this as well, though more so through language and stylistic choice, using parentheses and brackets to his advantage. As Losasso notices, “Schuyler asks his reader to look at the brackets, to hear them as they open and close, and to think about the spaces they create”, manipulating language to provide enough room for their own interpretation and feelings (160). In both cases, these poets are writing poetry in order to express themselves but in such a way there is no one meaning or definition of the poem and its purpose. However, this is not always achieved, and their real intent behind writing and their experiences comes through with metapoetical elements in several of their poems.

An apt starting place is Ashbery’s poem “What Is Poetry?”. This is a prime example of metapoetry due to the directness of Ashbery’s address to his struggle with writing poetry. There is an initial abstract scene presenting readers with a “medieval town, with frieze/ Of boy scouts from Nagoya? The snow/ That came when we wanted it to snow?”, which positions readers within a sort of landscape. Though descriptive, the words are vague enough together to create enough space to allow the reader to create their own vision of the setting. It can be argued this is to create a feeling even more than an idea or picture. Following these suggestions are several questions that address poetry and its complexity, Ashbery wondering about, “Beautiful images? Trying to avoid / Ideas? As in this poem?” He’s questioning his role as a poet and the importance of what he’s doing, no longer adhering to an abstract idea but a very concrete feeling and thought. He tells the reader he wants to avoid ideas, like he’s trying to do now in the poem, but he can’t seem to do it. However, he feels he has no choice, and compares it to returning “to a wife, leaving / The mistress we desire”, a vividly intimate way of describing the push and pull he feels with writing.

The pessimism continues with the next line criticizing the way literature and writing has been taught, where “In school / All the thought got combed out / What was left was like a field”, and the meaning has been removed. The return to a vague setting of a field opens the poem back up to the abstract form Ashbery was working with before breaking through to address his difficulty. The last line is also significant because of the dismissal of the genre and means of communication. By writing “It might give us–what?–some flowers soon?”, we are left with a sense of despair that the only thing we are looking forward to isn’t all that significant. This furthers the idea that Ashbery is frustrated with the form his writing takes and finds it somewhat futile, addressing this directly to the reader and also when returning to the abstract writing style.

Ashbery’s poem “Homeless Heart” typifies this again, though this time in the form of a free verse poem with a conversational tone. This poem explores the relationship between the poet and page, acknowledging the difficulty a writer has creating meaning while communicating this meaning in an important way. Immediately noticeable is the breaking from the “traditional” relationship expected between a writer and the reader. The writer presents something on the page, and the reader absorbs it and creates meaning from the language, style, and content. More specifically, the relationship between a poet and a reader comes with certain expectations – stylistic choices that could include rhyming, enjambment, imagery, precise meter, stanzas, and so on. This particular poem from Ashbery uses none of those, choosing to present what initially looks like a few sentences in a paragraph. Though still considered poetry, this loosening and expansion of form extends to an expansion of meaning and potential.

Our example of metapoetry here is in the beginning of the poem instead of further along, which creates an immediate desperation from the poet trying to explain himself. “Homeless Heart” begins with a lament, Ashbery confessing “When I think of finishing the work, when I think of the finished work, a great sadness overtakes me, a sadness paradoxically like joy. The circumstances of doing put away, the being of it takes possession…” revealing a writer who is struggling with his craft. It is the act of writing and trying to create that is painful, and the idea of the end goal becomes more important than the act of writing poetry for poetry’s sake. Ashbery laments this thought and tries to find a way out, deciding then to move along and change the subject.

While pondering the significance of his poetry, Ashbery takes these deeply personal ruminations and decides to minimize these feelings and thoughts, despite taking time out of his poem to explore them. Arguably the most important part of the poem is the line “Best not to dwell on our situation, but to dwell in it is deeply refreshing.”, because it is ironically referring to Ashbery’s own metapoetics and practice of writing about writing poetry. Through this break, Ashbery is describing the writing process to the reader directly, breaking the traditional form of an abstractionist poet and grounding one in what he is struggling with at the moment of writing. Ashbery finishes the poem with some intangible imagery, “As a box kite is to a kite. The inside of stumbling. The way to breath.The caricature on the blackboard.”, which could have any number of meanings depending on the lens you use. This return to conceptual statements after referring to the process of considering the act of writing is a return to a form that is comfortable, and now assumedly expected of Ashbery’s writing.

Similar to Ashbery’s poetry on the relationship between the writer and the reader is one of James Schuyler’s poems, which include the same metapoetics and self-referencing breaks of form that allude to a need for a different type of understanding. In “December 28, 1974” Schuyler positions the reader in a dark, wintery day, where the sun is setting at 4 o’clock and the sun is a “fiery circle” illuminating the room. The poet is contemplating his writing process, and reveals:

Still, last night I did wish—

no, that’s my business and I

don’t wish it now. “Your poems,”

a clunkhead said, “have grown

more open.” I don’t want to be open,

merely to say, to see and say, things

as they are.

Schuyler cuts himself off before saying something intimate, something he hopes for – “no, that’s my business and I/ don’t wish it now”. Like Ashbery, there is a push and pull between wanting to reveal oneself and feeling he has to remain reserved. He is faced with a deprecating remark from a “clunkhead”, supposedly someone who doesn’t matter or lacks intelligence, but whose words still affect Schuyler enough to write about them. In addition, this idea that his poems are “open”, whether that be open to interpretation or merely more accessible and not as deep, he is struggling with the form he feels both confined to and not good enough to write and resorts to metapoetry, pointing out this internal struggle to the reader. Towards the end, Schuyler says “the sun is off me now”; the spotlight is no longer on him to write these poems that bare his soul. Though a poet chooses the subject, depth, extent to which they reveal themselves through their writing, the reality is any form of art is a reflection of the person, who they are, and what they are trying to tell the world.

David Kaufmann’s work “Subjectivity and Disappointment in Contemporary American Poetry” reflects this difficult authorial goal of trying to remain objective but also leave room for the reader to assign their own emotion to a poem. Kaufmann asserts that a poem “…offers itself up not primarily as a report of an experience tout court but as a model of how the reader can address him- or herself to the world”, something Schuyler seems to be fighting in this poem (Kaufmann 233-234). While poets wish to write and remain closed off, they also yearn for understanding from their readers. Metapoetry is this vehicle to provide a window into the poet’s thoughts directly through their writing, ensuring certain ideas are communicated to the reader without interpretation.

John Ashbery’s “Buried at Springs” may not seem an example of metapoetry on the surface, but is another instance of a New York School poet using the art of poetry writing to stress a darker tone in the poem’s message. Springs refers to a hamlet of Easthampton out on the East End of Long Island, a place known for New York City dwellers to summer. Naturally, Frank O’Hara and several members of the New York School found themselves spending quite a bit of time here, and this poem is partially a dedication to O’Hara as Ashbery contemplates his friend’s time in Springs, as well as Ashbery’s own relation to the setting.

An intensely descriptive piece, the writing outlines Ashbery’s view from a window, first describing a hornet stuck in the room with him and the humanity in letting a hornet live instead of killing it. Describing the scenery with dark, vivid imagery of his view, this consists of everything from “rocks with rags of shadow” to “the thin scream of mosquitoes ascending”, a landscape that has been viewed favorably by others but negatively by Ashbery because of the association with O’Hara. The entire poem can be read as an homage to Ashbery’s esteemed friend, or to the New York School itself, because of O’Hara’s hand in creating the movement. But the references to Frank O’Hara’s writing and views from where Ashbery is sitting are metapoetical due to him referencing his current physical state of writing poetry at O’Hara’s desk. The excerpt below is from the first stanza, and shows the change in form and direction Ashbery suddenly takes while contemplating the scene:

it’s eleven years since

Frank sat at this desk and

saw and heard it all

the incessant water the

immutable crickets only

not the same: new needles

on the spruce, new seaweed

on the low-tide rocks

other grass and other water

even the great gold lichen

on a granite boulder

even the boulder quite

literally is not the same

He references O’Hara’s former presence where he’s sitting, reflecting on how “Frank sat at this desk and / saw and heard it all”, both physically and figuratively. While building a scene for the reader to imagine, Ashbery is describing what he sees but with reference to the way O’Hara viewed it, wondering if he’s seeing things the same way as his friend. Not only is he referencing his own current state of writing, but observing the practices of one of the most critical poets of the New York School. At the same time, he can no longer view the world the same because of the great loss of O’Hara, repeating through the poem “quite/ literally is not the same”, contributing to a duality in both the language and the poem’s title. “Buried at Springs” refers to not only Frank O’Hara’s physical burial, but the absence and removal of feelings, friendship, art, and much more to Ashbery. The presence of metapoetry in a poem so deeply personal yet with so many layers of meaning is another example of a poet’s need to break from his abstractionist writing and return to a direct address of his reader.

The inefficacy of both language and the abstract writing so typical of New York poets is professed through a noticeable pattern of metapoetry breaking the form of a poem abruptly, repositioning the reader to consider the poet’s direct and intimate perspective. Writers John Ashbery and James Schuyler are notable poets in their own right, recognized as innovators of a movement based in self-expression, spontaneity, and overall non-conformity. But the New York School’s basis in abstractionist art and its principles falls short, forcing writers to break from this vague style and return to directly addressing readers in order to express their ideas. Metapoetry’s presence in the New York School creates an interesting observation that even the most expansive and progressive schools have their limitations, and these find a way to show themselves through poetry.

_______________________________________________________________________

Bibliography

Kaufmann, David. “Subjectivity and Disappointment in Contemporary American Poetry.” Ploughshares, vol. 17, no. 4, 1991, pp. 231–49. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40350838. Accessed 18 Nov. 2024.

Losasso, Mae. Poetry, Architecture, and the New York School: Something like a Liveable Space. Springer International Publishing Palgrave Macmillan, 2023.

Nelson, Cary, editor. Anthology of Contemporary American Poetry. Vol. 2, Oxford University Press, 2015.

Nelson, Maggie. Women, the New York School, and Other True Abstractions. University of Iowa Press, 2007, Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/womennewyorkscho0000nels/page/n7/mode/2up.

Schneiderman, Josh. “The New York School, the Mainstream, and the Avant-Garde.” Contemporary Literature, vol. 57, no. 3, 2016, pp. 346–78. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/26445536. Accessed 31 Oct. 2024.

Web Links

Frank-OHara-Personism-A-Manifesto-1.pdf

Poems

John Ashbery – Poems by the Famous Poet – All Poetry

Buried At Springs by James Schuyler – Famous poems, famous poets. – All Poetry

EPC / James Schuyler: February

Paintings

La Grande Vallée XIV (For a Little While) | Joan Mitchell Foundation

Whose Name Was Writ in Water [Willem de Kooning] | Sartle – Rogue Art History

“Blue Poles” by Jackson Pollock – A Masterpiece of Motion

No comments yet.