Roland Barthes once wrote, “Subjectivity is a wound”. In other words, to be an “I” is inevitably tied to vulnerability and damage. It seems nonsensical, but our selfhoods depend upon the injuries we sustain: Had we been “uninjured”, we would have no interesting perspective to operate from, no history. In some sense, the “I” (…. the eye?) is an inscription or tear, to take the flesh metaphor to an extreme, the gash or psychic tear from which we gaze. Selfhood, scars, and character development all figure in the memoir of Safiya Sinclair and the autobiographical theories of Sidonie Smith and Julia Watson. Sinclair explores such in a more intimate and lived form — as a Jamaican immigrant torn between her new and old homes. She outgrows the shackles of her Jamaican father, in favor of a new life in America. Smith and Watson do something very similar to Sinclair, yet very differently: they explore the more historical and interpretative dimensions (of trauma) in their exploration of autobiography. Traumas all manifest differently, although the three concepts of conversion, the gaze, and captivity illuminate Sinclair’s.

Roland Barthes once wrote, “Subjectivity is a wound”. In other words, to be an “I” is inevitably tied to vulnerability and damage. It seems nonsensical, but our selfhoods depend upon the injuries we sustain: Had we been “uninjured”, we would have no interesting perspective to operate from, no history. In some sense, the “I” (…. the eye?) is an inscription or tear, to take the flesh metaphor to an extreme, the gash or psychic tear from which we gaze. Selfhood, scars, and character development all figure in the memoir of Safiya Sinclair and the autobiographical theories of Sidonie Smith and Julia Watson. Sinclair explores such in a more intimate and lived form — as a Jamaican immigrant torn between her new and old homes. She outgrows the shackles of her Jamaican father, in favor of a new life in America. Smith and Watson do something very similar to Sinclair, yet very differently: they explore the more historical and interpretative dimensions (of trauma) in their exploration of autobiography. Traumas all manifest differently, although the three concepts of conversion, the gaze, and captivity illuminate Sinclair’s.

Firstly, not all traumas are outright conversions, but many conversions are traumatic. Especially in Sinclair’s case, conversion, or simply moving from one state to another, is highly relevant. Initially, conversion might evoke a religious conversion, conversion therapy, political conversion, etc — all typically traumatizing events. At first glance, it seems inapplicable to Sinclair’s memoir. However, it can be expanded as a concept. Smith and Watson characterize conversion as an abandonment of one “self” in favor of “another”. In their words, “This narrative mode is structured around a radical transformation from a faulty or debased “before” self to an enlightened “after” self” (226). They suggest an original state of a “dark knight of the soul”, from which a person improves. Conversion, although less explicitly so, informs Sinclair’s story of acculturation into America. She “converts” from her Jamaican roots to elusive “Babylon” and its ideologies, a process both liberating and challenging. Her conversion to American culture is reflected in her writing in particular, to which her anti-Western father responds negatively. Sinclair recalls being compared to Shakespeare, but to her father: As she describes the encounter, “Oh.” I was surprised to hear it. Flattered even. “Thank—” “Him tell I man that you only write for white people,” he spat. His face taut, knotted. “You use their words. Not I and I words” (252). Her “conversion” to the Western canon is initially viewed positively — Shakespeare is a compliment. However, her father perceives it as a betrayal of her Jamaican roots. This complicates Smith and Watson’s framework: Conversions are not always wonderful and redemptive, towards some better end. To evolve as a self requires a killing of an old self. Again, “conversions” may be fraught with negative emotions: Trauma. They are frequently ambivalent, they reinvent towards a “new” self, but also the “betrayal” of an older self. One might look to forced religious, political, or sexual conversions as a parallel.

.jpg!Large.jpg) A trauma usually demands a witness. For it to be “legitimate”, someone externally must have witnessed it: Smith and Watson write about the significance of testimony and its unique variations in articulating a self-hood. They write, “As an act of being present to observe or to give testimony on something, witnessing suggests how subjects respond to trauma. The witness can be identified as an “eyewitness”, a firsthand observer … or a secondhand witness, who responds to the witness of others” (316). Witnesses and trauma directly figure in Sinclair’s description of a physical assault, to which she calls the police. Sinclair’s father even threatens to kill her — a “verbal” trauma perhaps. Her father immediately changes behavior once the officer arrives and discredits Sinclair’s accusations. She recalls, “My father smiled and shook his head. “This girl is a liar, Officer” he said. Every time he called me girl it was a calculated chisel purposely chipping me away” (305). She responds to him, “I’m not a girl” (305). Sinclair, in a sense, longs for a witness to confirm her suffering. The officer fulfills her longing for a “third-person”, someone to witness her and her father’s relationship, to correct it, justify it, and so on. As witnesses often do, however, they remain silent, and the cop does not avenge the abuse. The fantasy of a witness fails, and Sinclair is left alone with her family drama. Even the experience of reading a memoir is a kind of witnessing, and Sinclair creates the work for our gaze. Many philosophers (e.g.: Sartre) were fascinated by the horror of watching, and how an other can be made an object: This leads to captivity, or the imprisonment in another’s gaze.

A trauma usually demands a witness. For it to be “legitimate”, someone externally must have witnessed it: Smith and Watson write about the significance of testimony and its unique variations in articulating a self-hood. They write, “As an act of being present to observe or to give testimony on something, witnessing suggests how subjects respond to trauma. The witness can be identified as an “eyewitness”, a firsthand observer … or a secondhand witness, who responds to the witness of others” (316). Witnesses and trauma directly figure in Sinclair’s description of a physical assault, to which she calls the police. Sinclair’s father even threatens to kill her — a “verbal” trauma perhaps. Her father immediately changes behavior once the officer arrives and discredits Sinclair’s accusations. She recalls, “My father smiled and shook his head. “This girl is a liar, Officer” he said. Every time he called me girl it was a calculated chisel purposely chipping me away” (305). She responds to him, “I’m not a girl” (305). Sinclair, in a sense, longs for a witness to confirm her suffering. The officer fulfills her longing for a “third-person”, someone to witness her and her father’s relationship, to correct it, justify it, and so on. As witnesses often do, however, they remain silent, and the cop does not avenge the abuse. The fantasy of a witness fails, and Sinclair is left alone with her family drama. Even the experience of reading a memoir is a kind of witnessing, and Sinclair creates the work for our gaze. Many philosophers (e.g.: Sartre) were fascinated by the horror of watching, and how an other can be made an object: This leads to captivity, or the imprisonment in another’s gaze.

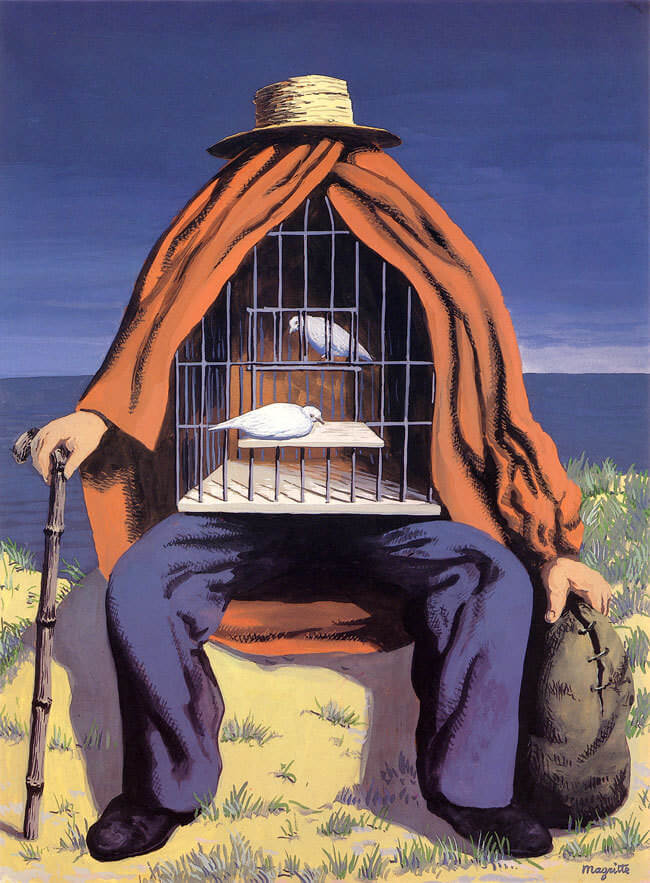

Indeed, the feeling of being a captive relates, though more implicitly. Sinclair writes, “I am learning how to be a Black woman in America. … Here in America I am a caged curio, a beast shaking the bars of her otherness. While every white writer stumbles sightless, their words directionless, their chatter thick with whiskey and Klonopin. Under their cold gaze, I have never felt more foreign” (310). Smith and Watson describe narratives of captivity and imprisonment: It is to feel like an imprisoned “other” in another’s jail. Smith and Watson characterize “captivity narratives” as “An overarching term for any narrative told by someone who is being, or who has been, held captive by some capturing group” (215). Sinclair is not literally in a jail or kidnapped: Her memoir nonetheless evokes one. Babylon, once liberatory, now seems like a prison: America. The literary establishment of America, as epitomized by medicated drunk white writers, worsens this caged quality. She feels captured by them, monitored by their privileged gaze. As if captive, she must “perform” Black womanhood for other Americans, despite coming from Jamaica. Unlike the previous concepts, captivity is not immediately traumatizing, as there is no singular moment or “injury”, e.g.: an assault. It is more gradual and subtly erodes the self. Still, it is traumatizing, although in more unconscious ways. What precisely seems to be an escape from trauma, only worsens it.

These three concepts from a distance do not have much to do with each other. However, in light of Sinclair’s memoir of trauma, they collaborate.

No comments yet.